Investigation into the ship loaded with ammunition and pickup trucks, searched in Greece but allowed to depart for Misrata, Benghazi, and Tobruk due to fears over migration. Photos, testimonies, and a letter from Operation Irini to the alleged trafficker: ‘Thank you for your cooperation.’ The case of the Aya 1 and its shipments from the Emirates

At the beginning of July, American intelligence alerted the European military mission Operation Irini to a suspicious ship. The container vessel Aya 1, sailing under the Panamanian flag, had departed on July 1 from the port of Mina Jebel Ali in the United Arab Emirates, and according to the AIS satellite systems, its declared destination was Terneuzen, in the Netherlands. However, according to U.S. sources, the cargo ship was actually heading elsewhere—Benghazi, in eastern Libya—and was not transporting cosmetics, cigarettes, and electronic equipment as listed in its documents, but rather ammunition and hundreds of pickup trucks for military operations.

Satellite images seen by Il Foglio show that on July 22, near Crete, the Aya 1 was approached by the Greek frigate Themistokles and the Italian frigate Francesco Morosini, both operating as part of Irini. The European mission, which came under Italian command in July, was launched five years ago to monitor the arms embargo on Libya. This time, however, things played out differently. According to at least four people with direct knowledge of the events—who chose to remain anonymous due to the sensitivity of the matter—the inspections carried out aboard the Aya 1 confirmed that it was indeed transporting hundreds of armored pickup trucks and ammunition destined for Libya, and from there to Sudan, for the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, better known as Hemedti, who is backed by the United Arab Emirates. Nevertheless, the Aya 1 was allowed to continue its journey to Libya. Il Foglio has reconstructed how and why Europe turned a blind eye to the violation of the embargo, and has also managed to identify the individual responsible for orchestrating this arms trafficking operation from the UAE to Sudan, via Libya.

The first to report on the suspicious cargo aboard the Aya 1 was the Greek newspaper To Vima. As required by the particularly weak rules of engagement that govern Irini, the mission command first had to request permission from the flag state before inspecting the ship. “The procedures for carrying out this kind of search are complex,” explains a military source. “That’s why, usually, when Irini obtains authorization to board a cargo ship, the inspection is thorough—and most importantly, the mission makes it public to demonstrate that it’s working.” In the case of the Aya 1, however, Irini’s communication channels remained unusually silent—perhaps out of fear of drawing too much attention. After inspecting the container ship in international waters, on the evening of July 27, the Italian Francesco Morosini escorted the vessel to the Greek port of Astakos, where it remained docked for the following four days. It was during this forced stop that an intense round of diplomatic negotiations began between Athens, Dubai, Brussels, and Tripoli—a negotiation that, according to Greek media, was being closely monitored by Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis himself. Jalel Harchaoui of the Royal United Services Institute in London explained to us that the matter was particularly sensitive for Athens: “The Greeks are in the midst of a dispute with the leader of Cyrenaica, General Khalifa Haftar, regarding the flow of migrants from eastern Libya to Crete, which reached an unsustainable peak between May and June.”

“Not to mention the dispute over maritime borders and the fiasco involving the European delegation expelled from Benghazi two months ago by the authorities in eastern Libya,” the analyst continues. “On the one hand, the Greek government didn’t want to upset its American allies who had flagged the ship, but on the other, it also didn’t want to further antagonize Haftar”. According to reconstructions, the solution Athens found was rather elaborate. First, it collected material proving that the United Arab Emirates had violated the arms embargo and sent all the evidence to the United Nations Panel of Experts on Libya. Immediately afterward, however, the Greeks requested that Operation Irini authorize the ship to resume its journey and deliver its cargo anyway. The workaround to avoid unloading the cargo directly in Benghazi—into the hands of the eastern Libyan authorities, who are not recognized by the international community—was to reroute it westward, having it pass first through the Tripoli-based government, which is recognized by the UN.

When contacted by Il Foglio, a spokesperson for the European Commission confirmed that “after receiving the necessary documentation from the Government of National Unity of Libya, and under the exemptions provided for by the United Nations arms embargo, the ship was authorized to continue its journey to Libya.” In essence, Brussels gave the green light to the delivery of weapons by channeling them through Libya and relying on the often vaguely interpreted exemptions that allow actions in derogation of the embargo. Thus, on August 1, the Aya 1 set sail again, but instead of heading to Benghazi as originally planned, it sailed to Misrata in western Libya, where it docked on August 4. According to military sources who prefer to remain anonymous, part of the shipment of pickup trucks was unloaded there—as also evidenced by a video recorded a few weeks later along the road from Misrata to Tripoli.

In the video (see below), at least three car carriers appear loaded with what seem to be dozens of beige Toyota Land Cruiser 79s, and likely also some Toyota Land Cruiser V8s—both models widely used in the ongoing war in Sudan. To avoid complications, the vehicles are sometimes armored only after being unloaded in Libya.

An investigation by the Center for Information Resilience (CIR), published a few weeks ago and based on the analysis of videos posted online by Sudanese fighters themselves, shows that these vehicles are being used by Hemedti’s men encamped south of al-Jawf, in the Sahara Desert and deep inside Libyan territory. From there, several military operations have been launched into northern Darfur, which have often resulted in massacres of unarmed civilians. Last week, one such RSF offensive led to the killing of around 1,500 displaced people from Darfur in the Zamzam refugee camp.

“The delivery of these vehicles to the Tripoli authorities was a kind of tip—perhaps a reward given by the Emirates to Libyan Prime Minister Abdelhamid Dabaiba for allowing the cargo to avoid being lost and still make it to Libya,” a diplomatic official told Il Foglio. As a result, part of the vehicles was redistributed among militias loyal to the Tripoli government, primarily benefiting the 111th Brigade, commanded by Abdul Zamad al Zoubi, who also serves as Deputy Defense Minister. The rest of the shipment left the next day, first headed to Benghazi and then to Tobruk, following an unprecedented route. Satellite images show unloading operations taking place at ports in eastern Libya. From there, the journey of the pickup trucks continued toward Sudan. Evidence that the delivery reached its final destination may be found in a video published last Sunday on X. It shows RSF fighters driving more than a hundred Toyota Hilux vehicles through the Libyan Sahara toward Nyala, in southern Darfur—a convoy that could be part of the Aya 1’s shipment.

Since the beginning of the conflict two years ago, Hemedti’s paramilitary militias have relied on military support from the United Arab Emirates, which is interested in controlling trade routes in the triangular area between Sudan, Libya, and Egypt. Among the Emirates’ preferred methods for supplying weapons to the RSF is an air bridge departing from Ras al Khaimah and Al Ain in the UAE, arriving in Benghazi or Kufra, areas of Libya controlled by their ally, Haftar. From there, the shipments travel south to their final destinations. Independent analysts like Rich Tedd, who has tracked UAE-to-Africa military supply chains for years, have documented this air bridge, showing it operates on an almost daily basis. “As for armored pickups, thousands pass through the Libyan desert toward Sudan—on average, there’s one shipment every three weeks,” the diplomatic source confirms.

The alternative to aircraft is maritime transport. Usually, it’s difficult to intercept and inspect cargo ships carrying weapons by sea. “Irini is hindered by bureaucratic complications that make it hard to stop and search suspicious vessels. And then there are the divisions among EU member states, who often use the mission to serve their own national interests,” a European naval officer told us. This was the case with the Greeks in the Aya 1 affair. However, this time the American intelligence alert forced the Europeans to act—just like in July 2024, when the U.S. ‘suggested’ that Italy’s Guardia di Finanza inspect and seize a suspicious container unloaded at the port of Gioia Tauro, which later turned out to be filled with Chinese-made drones bound for Libya.

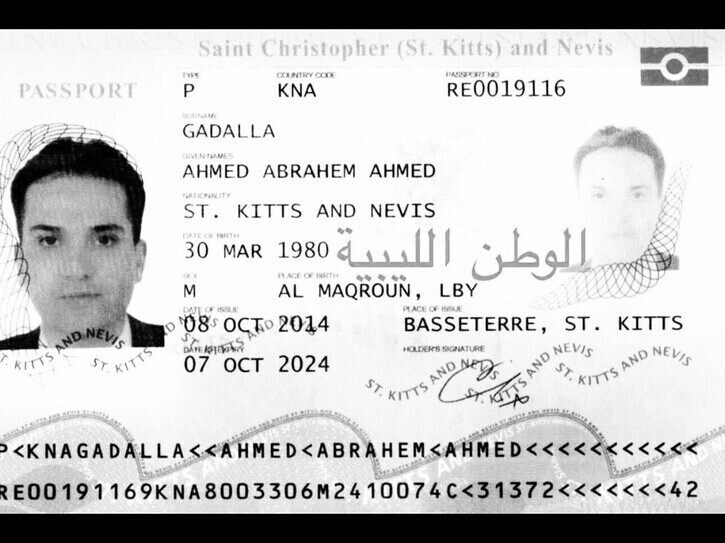

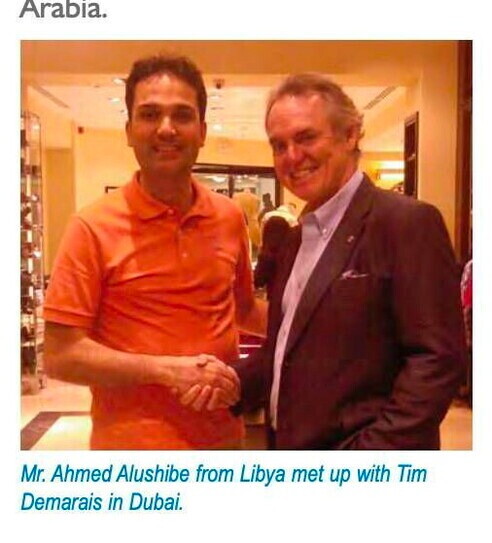

“When the Americans step in to curb arms trafficking to Libya, it’s because they have a direct interest,” a source explained. And in the case of the Aya 1, that direct interest has a name and surname, which Il Foglio was able to identify: the owner of the company operating the ship. He is a Libyan businessman, Ahmad Gadalla, described by those who know him as “a very dangerous man,” who owns multiple companies between the United Arab Emirates and Libya. Among them is the Alushibe Group, a logistics and international shipping company based in Dubai. According to Lloyd’s List Intelligence’s Seasearcher database—a portal that provides shipping data—Alushibe Group owns UDS Shipping Services LLC, based in the Emirates and listed as the commercial operator of the Aya 1. At times, Ahmad Gadalla goes by the name Ahmad Alushibe, as revealed by cross-referencing online data and photos from his companies with a copy of his passport obtained by Il Foglio.

The reason behind Ahmad’s dual identity may lie in some legal troubles he faced with the Emirati authorities between 2016 and 2018, as reported a year ago by the broadcaster Libya 360. While attempting to build his own business network in Dubai, Gadalla got involved with companies linked to organizations associated with Islamic terrorism. According to Libyan media, the American tip-off led Emirati authorities to arrest Gadalla, and at that point, it was Khalifa Haftar who interceded on his behalf with the Abu Dhabi monarchy, securing his rehabilitation. “The reason is that during the 2019 offensive on Tripoli, the UAE was one of Haftar’s main financial and military backers. That’s when they realized that a man like Gadalla—active between the two countries and with his own network—could be useful to both sides,” a Libyan source explains.

Il Foglio managed to reach Mr. Gadalla by phone, and he denied all allegations. “The fact is, I’m a very important businessman, and I’m seen as a problem by all the corrupt people who envy me because I’m doing great things for my country. They’re just trying to discredit me. I know nothing about these alleged arms shipments to Libya or Sudan,” he said, adding that he was currently in Germany to finalize a €400 million contract with Siemens—“but I also do a lot of business in Italy, with Danieli, for example.”

Gadalla also denied ever having been arrested in Dubai. “Some of my companies had dealings with others that were in trouble. They investigated me and found nothing. They only confiscated my passport for a few months, that’s all.” As for his dual identity, he said it was merely a convenience: “Gadalla is a very common name, whereas Alushibe is easier to remember.”

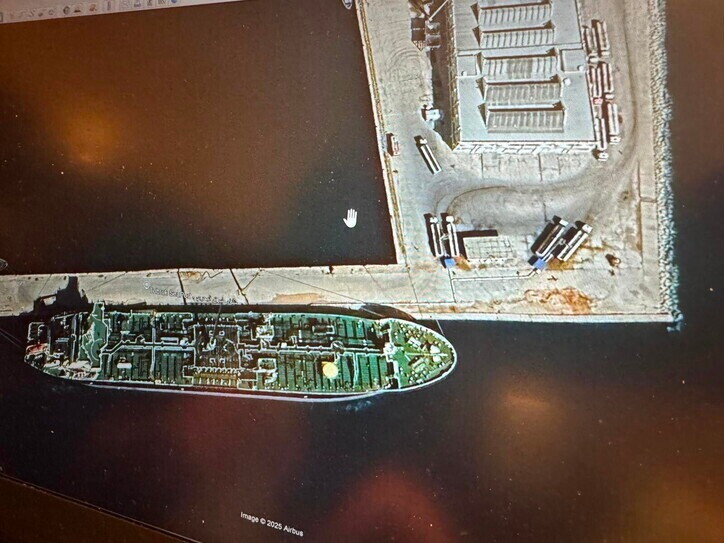

In any case, over the years, Ahmad has become one of the most influential businessmen in eastern Libya, holding a prominent role in the Benghazi-based Bank of Commerce and Development, which is led by Saddam Haftar himself. “He holds a privileged position—every time the Haftars need help or money, whether it’s for investments, international dealings, or contracts—they turn to him,” the Libyan source adds. “I’m the president of the world’s largest green steel factory in Benghazi. Of course I know the Haftars—anyone doing business in the east does,” Gadalla responds. “The Americans have been tracking him for a while because he’s also involved with Russians and Chinese in Libya,” says a person familiar with the matter. But that’s not all. What most concerned the Americans was the diesel smuggling. Satellite images show the Aya 1 engaged in suspicious activities this past March in Tobruk, eastern Libya. In the images below, the container ship is seen during what appear to be loading operations involving diesel, as indicated by the presence of 11 tanker trucks parked at the dock next to the vessel.

There are two anomalies in this photo. The first is that Libya is a major net importer of diesel, so it is strange to see a ship apparently engaged in exporting it. “Everything suggests this is an illicit operation,” says our source. The second anomaly concerns the very nature of the Aya 1, which, as noted, is a container ship—not a tanker.

“The method used to transport diesel is dangerous but effective if you want to conceal the cargo—it involves using flexible bladders hidden inside containers,” they explain. “The ship was tracked multiple times by the United States during these suspicious activities, but Irini wasn’t alerted until the cargo was believed to involve weapons and pickup trucks. Perhaps because they were hoping to catch them in something even more serious.” That may have been a miscalculation, given how things eventually played out.

“You should write good things about me. If you don’t, no problem—you’re free to do otherwise. But look, I have nothing to hide. No arms trafficking, no diesel smuggling,” Gadalla insists. “Just think: Irini even sent me a letter to apologize.” Indeed, the Libyan businessman forwarded us the letter sent to him by the European mission, signed by Italian Admiral Valentino Rinaldi, the commander of Operation Irini: “I express my gratitude to you for your kind cooperation with EUNAVFOR MED Irini,” the commander wrote to Gadalla. “I kindly ask you to direct the Aya 1 to the port of Tripoli for unloading under the supervision of the Libyan Government of National Unity. EUNAVFOR MED will proceed with the immediate release of the Aya 1.” Admiral Rinaldi’s letter is an important document for several reasons. First, despite its courteous and conciliatory tone, it is not a formal apology. Nowhere in the letter does Irini state that no material prohibited by the arms embargo was found on board the ship.

Secondly, the letter explicitly instructs the Ukrainian captain of the vessel, Antonyuk Volodymyr, to head to Tripoli. However, the Aya 1 ultimately sailed to Misrata instead—in direct violation of the European mission’s instructions. Finally, the letter orders the cargo to be offloaded in Tripoli, but satellite images show that part of the containers were delivered to Benghazi—and likely also to Tobruk, where the ship was moored for at least 19 hours—again ignoring the directives issued by the European mission.

And so, the Aya 1 affair was able to wrap up in just a few weeks—apparently in the best possible way for Gadalla. At least part of the cargo was delivered to its intended recipient in Sudan, and his ship was free to continue its activities. As of these past few days, the container ship is sailing through the Gulf of Aden, heading back to the very port where it all began: Jebel Ali, in the United Arab Emirates. However, in the coming months, the powerful Libyan businessman’s operations may face choppier waters, as the United Nations Panel of Experts is currently preparing its report on the Aya 1’s odyssey.

The article is translated with ChatGpt