PETALING JAYA: Educationists and disability advocates have urged Malaysia’s university admissions system to drop automatic course restrictions on persons with disabilities (PwD) following the recent case of an autistic student who was reportedly disqualified from entering a public university because of his condition.

They said admissions must move away from across-the-board restrictions and instead adopt case-by-case assessments that recognise merit and capability.

Universiti Teknologi Mara Shah Alam Faculty of Communication and Media Studies senior lecturer Dr Mohd Yusof Zulkefli said admission decisions should be based on academic performance, entry requirements and demonstrated ability, not assumptions tied to a diagnosis.

“In Malaysia, university admission decisions should not default to limiting course options for students with autism simply because of their diagnosis. The Malaysia Education Blueprint (Higher Education) 2015–2025 clearly emphasises widening access and ensuring equity.”

He acknowledged that certain programmes, such as medicine or aviation, demand specific competencies for safety, licensure or regulatory reasons.

However, he stressed that such limitations must be transparent, well-documented and applied only after thorough case-by-case reviews that consider reasonable accommodations.

Malaysia has taken steps towards inclusivity through the Persons with Disabilities Act 2008 and admission quotas in public universities. Some institutions have disability support units, but Mohd Yusof said implementation remains inconsistent.

“In countries like the UK, under the Equality Act 2010 or the US with the Americans with Disabilities Act, policies ensure that no applicant is disadvantaged unless there’s a clear and justifiable reason. International best practice prioritises universal design in learning, customised support plans and transparent admissions processes.”

He emphasised that autistic students can thrive even in demanding fields if provided with appropriate support, such as sensory-friendly learning environments, tailored orientation programmes, flexible but rigorous assessments, peer mentoring and lecturers trained in inclusive methods.

“These are not special favours. They’re reasonable adjustments that remove unnecessary barriers, allowing students to demonstrate their full potential.”

Mohd Yusof also urged the centralised university application system to introduce clearer pathways for persons with disabilities, including plain-language guides, infographics and videos.

He urged the Higher Education Ministry to replace automatic restrictions with capability-based assessments, provide pre-application consultations for PwD applicants, update entry requirements in line with assistive technology, strengthen disability support units and publish annual data on PwD admissions and retention.

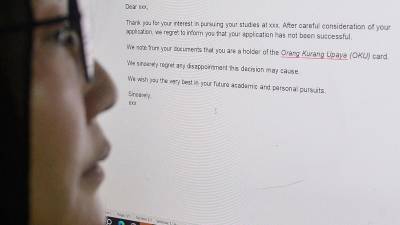

The autistic student, identified as Aniq, scored a matriculation GPA of 3.83 and met all entry requirements. However, during the third phase of the admission process, his chosen courses were removed from the system.

Higher Education Minister Datuk Seri Dr Zambry Abdul Kadir said the ministry has opened an investigation and pledged a quick resolution.

He assured that Aniq would be offered a place at one of the universities he applied to, adding that the International Islamic University Malaysia is also reviewing his case.

National Autism Society of Malaysia chairman Julian Wong echoed these concerns, warning that systemic barriers still persist in higher education despite greater awareness of autism at school level.

“High-achieving autistic students often encounter roadblocks not because of their ability, but because of outdated policies and lack of inclusive practices.

“Some course restrictions may amount to indirect discrimination. Even if not intentional, the effect is the same – capable students are denied opportunities they’ve earned.”

He also called for applicants to be considered as individuals, not categories and for universities to appoint dedicated support officers to bridge students and academic departments.

On the idea of a dedicated higher-learning institution for special-needs students, Wong said such a facility could provide targeted resources, specialist educators and integrated support. However, he cautioned against the risks of segregation.

“A separate university might unintentionally create segregation, limit interactions with diverse peers and struggle with sustainability.

“With the right opportunities and support, students with disabilities, including those with autism, can excel in the most demanding disciplines. We must shift from asking, ‘Can they cope?’ to ‘How can we enable them to thrive?’

“Inclusive education is not charity. It is about unlocking potential. An inclusive Malaysia is one in which every individual, regardless of ability, has an equal opportunity to pursue his or her dream.”